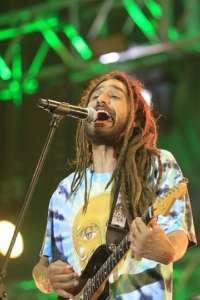

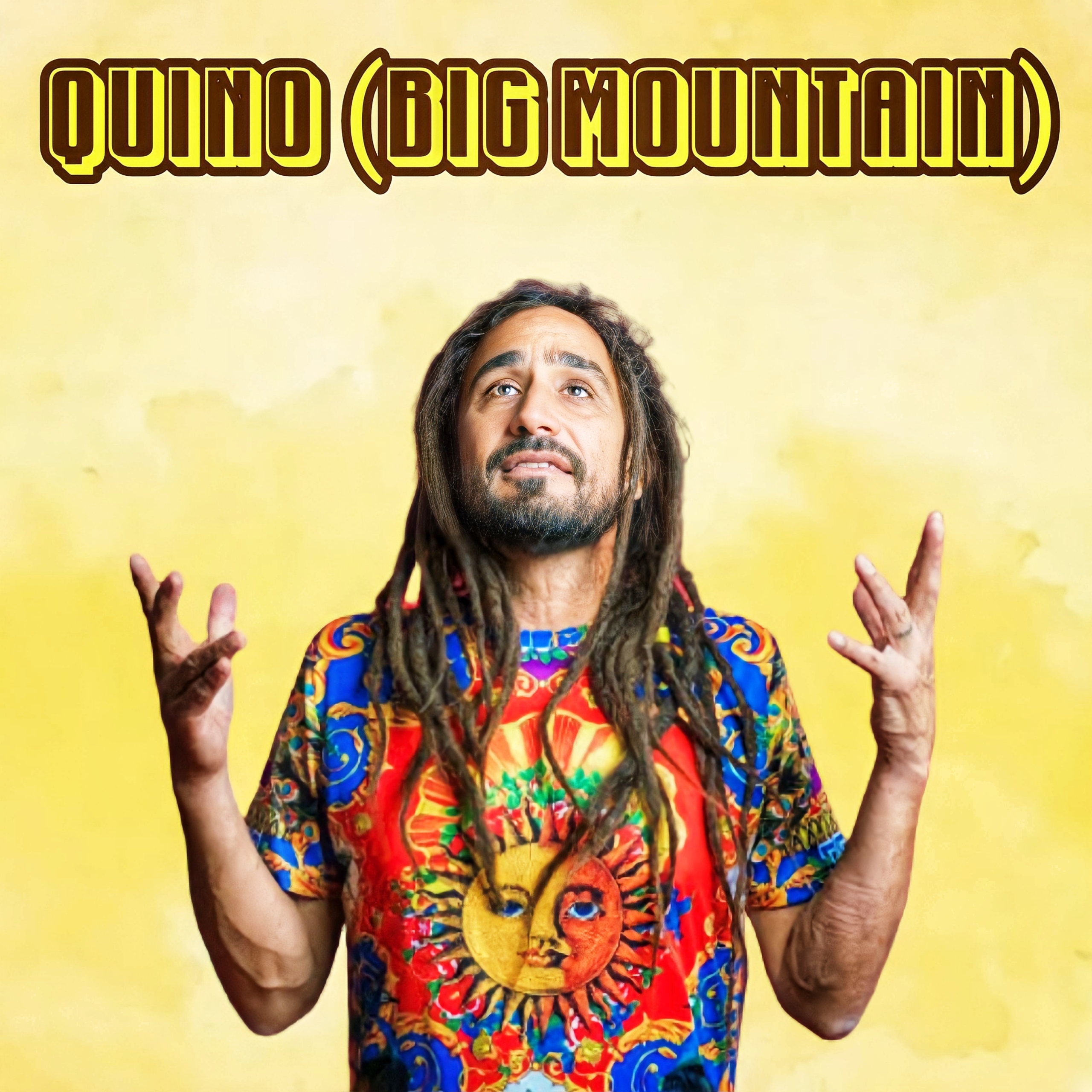

For the umpteenth time Joaquin ‘Quino’ McWhinney, the singer of ‘Baby I love your way’ set foot on the Indonesian archipelago. His arrival at the end of 2022 was in the framework of a series of shows in three different places in Indonesia namely Bali, Jayapura and Medan. In addition to traveling shows, it turns out that he is also working on a collaboration single with Marapu Band. Even in the midst of his busy schedule, Kultur.media is grateful to have the opportunity to conduct a question and answer session with him through a video conference connection. With great enthusiasm and friendliness, Quino was willing to share his story with all of us. The following is an excerpt of his chat session:

How did you first get acquainted with reggae music?

My first experience with reggae music was watching a news program with my father. I was probably about 14 years old, and it was a Sunday night news program called 60 minutes in the United States and they had an episode about Bob Marley, reggae music, Rastafari, Jamaica, Ganja, the whole thing. It was probably around 1978 or something and had a heavy impact on me. It really grabbed me. I could tell that was the first time I saw Bob, first time I heard anything about reggae music and I could tell that Bob was different. The music that he was singing about is very important to him. It wasn’t just any other kind of music.

Other than Marley, who else at that time?

At that time? Well it was just Bob Marley for a while, you know. Reggae was still…It was still very difficult to get the whole of any artist you know, the record store really didn’t have a very big name. I can remember Eddy Grant on the radio shortly after that but you know by the time I think when it was about 1981/82 I think that I started to see band live. I never got to see Bob. Bob died. I remember the day that a friend brought me a newspaper, you know. I had still never seen any live reggae music. But one of the very first bands that I saw live was Steel Pulse, and that was a really big experience. I saw Black Uhuru, an early formation of Black Uhuru with the whole original line up: Michael, Puma, Duckie, Sly, Robbie. I did get to see Peter Tosh, I saw Jimmy-Tosh, I mean Peter Tosh and Jimmy Cliff together in the same concert. They had a tour together. That was an amazing concert. I really enjoyed that.

When did you start to make your own band? Playing music?

It was in high school when I started, we would have jam sessions in the garage. I graduated in 1984 so this would’ve been like around 1983, I would’ve been about 16 or 17 years old when I started to form a band. I really didn’t perform out with anybody until I had already graduated from high school, probably like age 21? I first started out as a background vocalist and a percussionist in a band called ‘CornerStone.’ And then I started my very first band called ‘Rainbow Warriors’ and that evolved into a band called ‘Shiloh’ and then ‘Shiloh’ turned into ‘Big Mountain.’ Our first time in the studio was probably around 1989 or probably 1988. I recorded my first full album in 1989 or 1990 and that was the band called ‘Shiloh.’

Are you doing a solo now or still with the band? Cuz’ you’re coming to Indonesia by yourself. Some say they missed seeing you perform with Big Mountain.

Yea, I would love to come with Big Mountain, you know, and Big Mountain is still together. As soon as I’m done here in Bali, on December the 7th I fly to India and I’ll join Big Mountain there. We’re gonna play in India for three weeks. So yea, find me a promoter that wants to bring Big Mountain and I’ll bring Big Mountain [laughing]. You know when I’m not busy with Big Mountain, I have to keep working, you know, got to keep working. And I like to get out of the United States. I do a lot of stuff in Latin America right now, Mexico but I like Asia. I really enjoy Asia. And you know, not a lot of reggae bands touring in Asia. I like to take risks. I enjoyed traveling by myself. It’s nice to go with the band, Big Mountain but traveling with the big band creates obstacles sometimes you know. Sometimes it makes it difficult for you to get to know the people and spend time with the culture of where we’re going.

Can we expect a new album coming up with the band? Maybe next year?

Yes ! We’re just about to release an album. First single will be released in December and the whole album will be released by March. Yes

What is the title of the Album?

The Title of the album is ‘The Return of the Goddess’

We have noticed that you’ve been to Indonesia several times. In 2011, there was a reggae festival. Was that your first time in Indonesia?

First time in Indonesia was in 1994, we came to do some promotion in Jakarta, and then we also played in Bali. With reggae sun splash came to Indonesia in 1994. It was a huge tour. Huge tour, it was Big Mountain, Inner Circle, Marcia Griffits, Freddie McGregor, Maxi Priest, Cindy Breakspear.

In Bali? (we didn’t know that)

Yea in Bali, 1994. reggae sunsplash.

So what is so special about this country that makes you keep coming back?

The people. You know, the people in Indonesia just got a really nice balance, nice blends of energy for me. It’s hard to explain exactly. I mean there’s nice people everywhere. But also the environment you know, it’s just beautiful, a lot of beautiful beaches, the food in Indonesia. But it’s the people, definitely the people. People are very special here.

You have plenty of catalogs. But we would like to highlight a song that has a connection to Indonesia. It is ‘End Of The Day’ (Hari Kiamat) , a song by Black Brothers, a band from Papua Indonesia. Can you tell us about how you decided to do the song?

When I came here in 2011. I came as a guest of Mr.Boy, the promoter of the International Indonesia Reggae Festival. And it was his idea. He invited me to do the song and asked me to do a collaboration with him. So I agree.

Who is Mr. Boy?

In the record, I think he called himself Papa Reggae. But he was the promoter. He was the person that financed that tour. Yea, so the person that I’m doing a collaboration with. It was his idea to do the song and I agreed to do it.

Did you know that the song was written by Black Brothers?

Yes I know, I know from August Rumwaropen from Black Brothers, from Papua. I’ve collaborated with the daughters of August, ‘The Black Sistaz’ in Australia. We did a song together called ‘Vision.’ It was produced and written by David Tweedie. I went to Papua New Guinea, in Port Moresby, maybe about 8 years ago and I met them. I met Black Sistaz there. They came up and then talked to me. They introduced themselves to me, and then they told me that I had performed their daddy’s song and we ended up doing the song together. I know it was a controversial struggle. We can’t really talk about what’s going on in Papua much but it was a song to support the indigenous people of Papua and I took part in that song. It was an album that was dedicated to the indigenous people of Papua.

Did you write the English version of the song?

Yes, I translated it to the best that I could.

We’re sure that you also use music as a medium to educate and build awareness about issues in society. Is there anything in Indonesia that you’re concerned about and feel needs special attention?

Well I performed in Papua Indonesia two weeks ago and some soldiers came in and they stopped the show right in the middle of my music. They stopped the music. They came in, they searched everybody and asked everybody for identification. I don’t see that happen in Bali. So yea, I can see that the way the government treats the people of Papua is different. I played many shows in Bali. I never saw soldiers come in and stop the music. So yea, that’s concerning. That’s very bothersome. I don’t really know what’s behind it. I know it’s a very complicated issue that the government doesn’t want us to really talk about which is uncomfortable you know. We should have freedom of speech, we should be able to express ourselves, we should be able to say whatever we want, you know. It’s kind of a hush hush, so that’s frustrating. But you know, I like Marapu’s approach. My brother Yanto, the singer of Marapu, he’s doing a lot to sort of promote Sumba, his island, the culture of Sumba and that’s nice to see. I know in Sumba there’s some religious freedom. That’s positive. You know reggae music, you can’t stop progress. You can’t stop progress from happening and people wanting their freedom. Have you ever heard of the term ‘The stones that the builder refused, shall be the head corner stone?’ The Wailer they sing that? [singing] right? That ideas and struggles that are proposed today may seem new, they may seem strange but in the future they will be accepted. You know that’s the whole idea that the stone that the builder refused. What is refused and what the government or society try to suppress today, in the future will be the head cornerstone, will be the thing that the people rally around. So you know, you can try to keep the people down but it’s only gonna be for a certain amount of time and then the people end up deciding what is right and what is wrong for them.

You have a busy schedule to perform here in Indonesia, from East to West, Sumatra is the Next stop. What do you think about the reggae massives here in Indonesia?

It’s just great to see reggae music and the Indonesian people making reggae their own, and the Indonesian people are using reggae the way reggae is supposed to be used. Reggae is supposed to be embraced by the people and the people use it to express their hopes and their pride, their culture pride. And to express their frustration with the system. So that’s how reggae makes the change and helps to heal, right? I mean, I think reggae music is a real important tool for this world. We went through a long history of colonialism when European powers controlled the world, right? It happened here in Indonesia. It happened in Africa, it happened in the Caribbean, and now the world is moving pass that era and we’re finding ways to get back to our roots again and that’s where reggae music is best at. It is helping colonial people because you know, my roots are Mexican. I live in a country that tries to make Mexican people invisible but we’ve been there all along right? Mexican people, we’re indigenous people, Mexican People are Indians, right? So we’ve been there for at least twenty thousand years, maybe more, maybe 40 thousand years, the government of the United States for political reasons doesn’t want indigenous people to have a voice. Reggae music is what connects indigenous people back to their land, connects indigenous people back to their culture so that we can heal. Heal from this time of colonialism, slavery and exploitation.

What is your special place in Indonesia?

You know, everywhere that I find time to spend with the people is very special. I know that here in Sumatra I won’t really have a lot of time to connect with the people, I’m sure this place is really beautiful. Now I’m just in a hotel, in the city and you know we’re not gonna be here that long I don’t wanna go out you know. I have to focus on the show tonight, I have to focus on my performance so I don’t wanna go out and get tired and try to do too much right?! Bali is a beautiful place. Bali has this very special charm but there’s a lot of people in Bali [laughing]. One place that I’ve been able to really spend time and connect with the people is Papua, Jayapura. The people in Jayapura called me ‘baptu’ (bapa tua). Which I guess means like uncle or something like that. Everybody called me ‘baptu’ there, you know. They treat me with so much respect and it’s such a very special place. So Papua has a very special place in my heart. There’s my brother Gorby. It’s because I’ve been able to sort of spend time there, but also Marapu has been a great host for me. I love the band, I love the style of their music. I think Yanto is a great singer, great songwriter, and so you know, I really look forward to doing more work with Marapu. We recorded a song while I’m here, a collaboration between Big Mountain, Marapu, and an artist from Chili named Tiano Bless, you can find him on spotify. We’re gonna be recording a video on Thursday, on that song in Bali.

Well you mentioned ‘Gorby ‘before, you went to Papua and did a show with him. You’ve made a collaboration with him and his band. It’s a great thing to do especially for the musicians in Papua. What motivates you to collaborate with them?

O there would be a little bit of history. You know, like you said the connection with the Black Brothers and from the Rumaropen sisters, they are good friends of mine, and I sympathize much with the indigenous people. The whole purpose of Big Mountain, the reason we were named Big Mountain, is because our struggle of indigenous people in Arizona in the United States. The people were being relocated because of a mine, because of a coal mine, so you know this is a world wide struggle This is a struggle of indigenous people being able to maintain their tights to the land, their respect in the face of capitalism, in the face of this global neo liberal world where corporation can move in and out of a country but people can’t move right? You know, for Indonesians to get a passport to go on vacation to the United States is very difficult, but for corporations in the United States to come to Indonesia and take gold out of the land is very simple, very easy. That’s not right. It’s not right, it’s not fair. That shouldn’t be legal. Reggae music is a way for us to change that but like you say we have to keep, we have to stay conscious and we have to be strategic right? We can’t just fight all the time. We have to find ways to make our voice heard in other ways besides using the military, besides using violence, because we know that we have to continue to live. Yes, we want to change this world, and yes, we want to dedicate ourselves to the struggles of indigenous people but we also want to live our life. We also want to see our children grow, we also want to spend time with our family, have gatherings and enjoy this life. Not be running away from Babylon all the time, right? So it’s a very difficult balance. One thing that you cannot fight against is music. Music is the most powerful way for us to send our message and for Papua that’s gonna be an important tool to have. The ability to send their message and to preserve the culture of Papuan people through music. We need to protect the songs of our old songs, the songs of the original people right? We need to protect the culture and the traditions. Not just with reggae music but with traditional songs. We need to protect traditional songs but one way that we can inspire is to use reggae music to inspire the youth to preserve your culture, preserve your languages, preserve your connection to the land. There’s many ways to do it and reggae music is a very powerful way to do it.

Are you going to perform with Gangsta Rasta tonight?

Yea Gangsta rasta, Tony Q Rastafara is here, so yea it’ll be nice and it’ll be nice time to you know, to enjoy some Indonesian reggae.

It’s a standard question to every guest in Kultur. Reggae for party or conscious reggae? What do you think about reggae music nowadays generally?

Well you know,I was part of the generation of musicians, that we were like the first generation after the death of Bob Marley, right? And maybe like the first time that reggae music really started to make its way outside of Jamaica. I remember that our main preoccupation was getting reggae on the radio, and we all kind of feel that wow. It’s crazy radio doesn’t support reggae you know, back then nobody wanted to play Bob Marley. Radio didn’t wanna play Bob Marley right? And we just thought that was very unfair and wrong so we sort of made some compromises to get our music on the radio. Started to add influence of R&B, and rock, and rap music to make it be accepted by record companies, radio and the music industry in general. And it was just what we were trying to do to make reggae music move forward. And out of that, some people got a wrong idea about reggae music and a lot of people around the world, the industry promoted the party party part of it but didn’t promote the other music that we were singing which was about revolution, was about cultural identity, which was about post-colonial repatriation with our ancestral homelands, and our ancestral culture. So you know, I’m one of those people who if I could just play roots music all day long I would do it, but life got a little complicated. I wish I would’ve kept my life simpler and I would’ve just not had any children or figure out a way to live somewhere not in the United States where United States is so expensive [laughing] I would love to take my family to a little island somewhere and live somewhere where we can fish and eat all day [laughing] and grow our food in our garden but that’s not reality you know. We have to work. We have to continue to generate money. Life is a balance and I think that made Bob successful. I mean lets be honest Bob was a pop musician so that was what set him apart from a lot of artists that were coming out of Jamaica. He knew how to fuse the music. He knew how to write songs and some of his songs are pop songs that are more popular than pop music and then they were manipulated by Chris Blackwell from Islands Records. A lot of overdubs were done and then post production was done, and Bob did the same thing. We took that strategy, bands like Big Mountain , Inner Circle, Maxi Priest, Aswad, we used that strategy to continue on Bob’s method of getting more exposure and getting mainstream music to accept the music. It was nothing new. We were just following by example, but again you know life is about balance. Everything in life is about balance and you know some of us that miss the good old days of reggae can sort of control the messages right? We can control the concept of reggae. It was a little bit easier for us to wrap our heads. Now reggae is worldwide and there’s also some types of reggae and some people think that reggae’s purpose is to have a party. Some people think that reggae’s purpose is to express more revolutionary concepts and messages. Everybody thinks that they invented reggae music [laughing] you know. I was joking around. They said in the reggae community everybody is a star right? Everybody thinks that they were the first discovered Bob Marley and everybody is a star right? Even the person that sells the jerk chickens and the festivals sometimes has more instant followers than me right? [laughing] Everybody makes reggae music as a very personal journey for them. And I guess that’s what it’s supposed to be.

What is your own point of view about dancehall music, I mean dancehall artists like Shensea, Vybs Kartel, Spice?

There’s always gonna be the element in music you know. It’s just part of being human, right? I mean it’s impossible for us to remove certain things, especially in a world that suppresses our sexualness, in a world that suppresses the human body. They try to deny the human body, you know. People we all feel, we can all smell, or we can all see, we can all hear, we can all touch. It’s just part of being human and we all long for that desire to be able to connect with somebody sexually and feel somebody and when you live in a world that tells you: “no! you’re not supposed to do this, you’re not supposed to do that, haram, sins, you know [laughing]. There’s always gonna be those people that just go crazy and say No I’m going to completely rebel against that and I’m going to not only am I going to rebel but I’m going to throw it in your face right? There’s always gonna be the element and you can go back to the earliest times, there’s gonna be what Babylon is all about, right? You go back to biblical times and Babylon was the center of sins, prostitution, gambling, “Self-indulgence,” sexual indulgence, materialism. Some of us have these desires to try to live as pure as possible but deep down inside we do feel the urge to just let go and go get a bottle of alcohol and forget this world and let our minds not be constrained by this. It’s not our job to judge. I really think that we have to do what allows us to sleep at night.

Just like the scriptures say that you can’t throw stones because we all live in a glass house. We all live in a house that buries our soul. So focus on your thing, if it bothers you then live up to those examples that you don’t think should exist. But going around saying oh you’re bad, you’re wrong then you’re never gonna stop. The whole world is filled with examples that are going to disappoint you. Focus on what keeps you whole and stunned.

Last year there was a controversy about SOJA winning the Grammy. It was triggered by an accusation I can say about cultural appropriation by non-Jamaican (white) artists. What do you think about this issue?

Well, as you might imagine, I received my fair share of criticism. I was one of the early targets and it did hurt, it affected me. I left reggae music for almost 10 years. Actually, the Indonesian reggae festival was one of my first shows after almost 10 years. I went back to university and put Big Mountain to sleep. I went to teach in high school. I taught high school for 8 years. And part of it was because I was tired of the controversy. Big Mountain received a lot of negative retention, but I understood it ,you know. And it wasn’t just that, it was also with the record label, a kind of fight with the record label. Record labels not allowing us to do what we wanted to do. We were very much controlled and told what to do, so you know, there were a lot of reasons why I decided to take a break. But maybe that’s why Indonesia is so special to me. Because the first big show that I had was the Indonesia Reggae Festival and on that trip we went to Gili and I remember I was in the water in Gili swimming and I was feeling good. It was the first time in the water that I really felt relaxed and happy on a musical level. It was just nice to be in Indonesia. It was very nice to know that Big Mountain was a part of people’s life in Indonesia. I started to grow my dread again [laughing] It was in Gili when I was in the water and decided to grow my dreads. ‘Baby I love Your Way’ came out in 1994 and I cut my dreads in 1995, a year later and I was already tired of music, I was already tired of the music industry, I don’t wanna be the most famous rastaman in the world anymore. And you know, I didn’t have dreads for 15 years. and it was here in Indonesia where I decided to grow dread again.

So can we say that’s your revival to get back to the music again?

yes, very much so. Yea, there was something about Indonesia that gave me strength. I think that inspired me because there were many years that I stopped writing music, I stopped having a desire. I just couldn’t make sense of the music business. I just lost the fire, you know. I lost the fire that I’d had with Big Mountain on those 6 albums. It just seems like everything that I tried to do, it came up wrong and I was not happy. I was not happy being on the major label, and everything was so different from what I had imagined it in my head [laughing]. So I left and I went back to university and I studied and I got a job teaching. And it was good. It was good for me to do that, you know. It was good for me to live that life and now I come to music with a different perspective and appreciation.

Being a reggae singer is actually a teacher, right? Isn’t it?

[laughing] It is, it really is. That’s one of the things that I love. I love to play with a lot of different bands, you know. I mean Big Mountain, I love my band, I love being on the road and play with them but being with a band like Marapu allows me to give some knowledge you know and share knowledge and also connect with different people in a very intimate way, you know. People from a different culture in a different country but still communicating through the medium of music. It’s a beautiful thing.

(Yedi)

Show Comments (0)