The first time I heard the term Reggae Revival was when I explored the work of Protoje feat. Romain Virgo. More than just a song title and music style, Reggae Revival turns out to be a conscious movement that wants to bring back the spirit of conscious reggae into contemporary music. An effort to restore the spirit of the legacy that was established by its originators in the golden era of reggae in the 1970s.

In welcoming the reggae month this February, which coincides with the birthdays of two of its forerunners, Bob Marley and Dennis Brown, Kultur also would like to celebrate it by sharing the story of the Reggae Revival’s movement despite the controversy since its emergence fifteen years ago.

Specifically, Kultur wants to look at the history and the cultural and political work done by the collective knowledge mobilization by the Reggae Revival movement. How does the history of the past influence the production of culture in the present. Where did Reggae Revival come from? And what are its broader social goals?

History

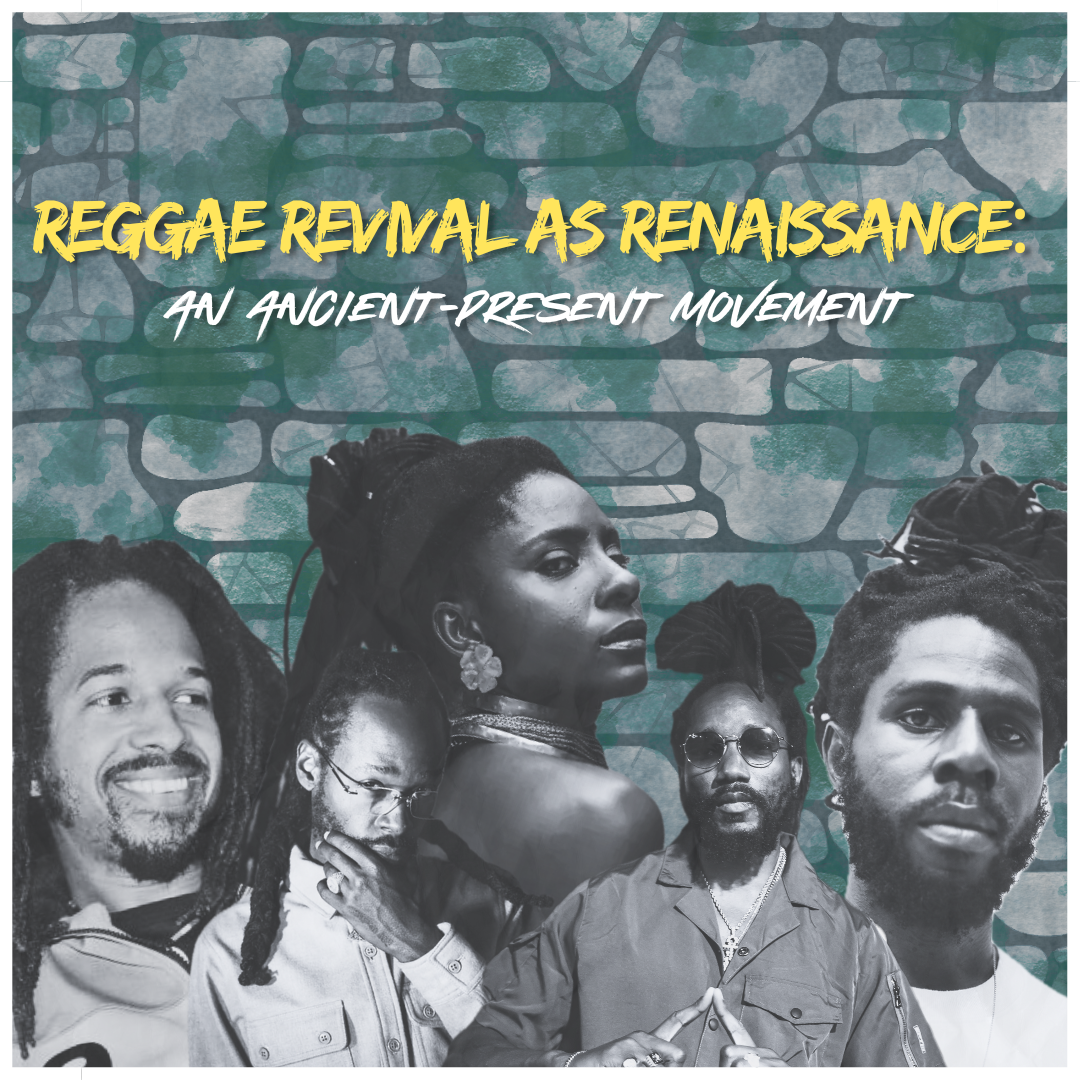

Most of you must already know that this group of Reggae Revival artists is synonymous with musicians such as Chronixx, Protoje, Kabaka Pyramid, Jesse Royal and Jah 9. It turns out that all of them are affiliated with an intellectual community known as Manifesto Jamaica.

Carrying the spirit like the ‘Harlem Renaissance’, this community originated in the early 2000s with a collaboration of intellectual groups and creative industry workers including managers, publicists, and community activists. Pioneers such as Gavin ‘Dutty Bookman’ Hutchinson, Lesley-Anne Welsh and Kareece Lawrence were united in wanting to engage young people across Kingston in arts and culture. Some of them were school friends who went on to work in the music business after graduation. Welsh works as an assistant to the Marley family, Lawrence works as an event organizer, and Bookman is a tour guide at the Bob Marley Museum and a youth community activist.

The term Reggae Revival itself was first coined by Dutty Bookman on November 22, 2011 when he released his book entitled ‘Tried and True: Revelations of a Rebellious Youth’. The naming serves two purposes: to unite the music wing of Jamaica’s Manifesto community movement under a name that emphasizes its connection to reggae’s long history and to become a cornerstone in the effort to frame its own narrative regarding the Revival’s vision and mission in a proper way.

Bookman, who is said to have had many mystical and spiritual experiences, says that there is an invisible vibration that influences and perhaps even dictates what humans can do. That vibration is like a moral pendulum whose movement is a manifestation of the swing towards righteousness. He says that “We attack injustice through our art and our music—it is our cultural weaponry.”

Music is the best hope for this intervention because of Jamaica’s reputation for its globalized cultural legacy. The hope of a group of touring artists traveling the world together as a collective representing Jamaica and Rastafari in what is referred to as ‘Oneness’.

In particular, Reggae Revival wants to bring back the spirit of conscious reggae as an inspiration for urban youth and an antidote to the influence of gangs, violence and degradation that are present in the political climate and musical subtext in dancehall that is currently dominating Jamaica. Of course, without discrediting dancehall and the contribution of early artists such as Sizzla Kalonji, Fantan Mojah and I-Wayne who are considered as the first wave of conscious reggae in spaces that are more similar to dancehall like the Reggae Revival group today. The re-popularization of conscious reggae through the themes of Rastafari, Livity and Pan-Africanism is the result of a wider global moment in raising individual and collective consciousness.

Starting from ‘Reasoning’ in 2009, the group was finally formed which also involved Natalie Reid, Rita Marley and Donisha Prendergast (daughter of Sharon Marley). They are under the banner of Manifesto Jamaica as a non-profit program or NGO to educate, expose and empower the youth of Kingston through the arts. Their activities are multi-disciplinary and diverse such as conducting workshops, seminars, and free medical treatments, and also organizing an annual Art Festival, ‘ART’ical Empowerment.’ They believe that creative practice and creative industry work can serve as agents of personal, communal and national empowerment.

The group formed a partnership with the Canadian-based organization Manifesto as well as the Canadian government funding agency, the ‘Canada Fund for Local Initiatives’. They also received assistance from the Jamaican Social Development Commission in sponsoring the first festival.

The inaugural ART’ical festival was held on August 19, 2010 at Bookophilia bookstore in Kingston and was covered by the Jamaica Gleaner. The event began with a performance of the traditional ‘libation’ ritual rooted in the Igbo and Akan cultures of West Africa, a heritage ritual in which performance practices connect actors with their ancestors in spirit. There were also poetry readings and musical performances by local artists.

Esprit de band

Musicians also gather at ‘Jamnesia,’ a surf camp and art rendezvous in Kingston, for weekly Jam sessions on Saturday nights. These live music performances emphasize the full band instrumentation used by the musicians, which continues to grow as Revival grows.

Playing reggae live with a full-band is one of the missions of the Revival movement to restore the organic sound that characterizes roots reggae. For them, this is politically and culturally meaningful.

Despite the financial challenges (it is much more expensive to tour as a full band than as a solo act), bands such as Raging Fyah, No-Maddz, and Pentateuch are becoming increasingly popular. This emphasis on collectivity extends to the development of contemporary music industry settings in Jamaica as seen by Chronixx as one of the Revival musicians. Playing together, according to him, is a more holistic approach.

He said: “It started more with the content and our approach to music. We try to make holistic music, even on our computers, you know? But whenever we performed, we wanted real guitars, real drums, real everything.” This ‘Esprit de band’ can also manifest in many interesting ways.

Revival’s activities gradually began to receive widespread attention and coverage especially by reputable media such as the Gleaner. The reverberations motivated a variety of agendas and vigorous programming such as creating a weekly radio program on Kingston’s Roots FM, doing more performances, art demonstrations, vocational film training and other arts-based events that support narratives of musical and creative significance in Jamaica. Its members manage and promote the Revival group, using each other for bookings and collaboration. Its social media channels promote activities such as camps, open-mics, which provide social networking and performance opportunities for professional and up-coming musicians. They believe that the arts can unite Jamaican youth by opening up new channels of communication, creating opportunities for sharing and collaboration and strengthening networks and community ties.

Togetherness is important to the Manifesto and Reggae Revival communities because they believe that individual success will not lead to the cultural improvement and collectivity they aspire to.

Self-sufficiency

In relation to the music industry, Manifesto Jamaica also created the Jamaica Music Conference which addressed themes close to musicians such as market preparedness, copyright management tools, and other industry strategies. Lawyers, industry professionals and renowned artists provided panel discussions, workshops for management and early career reggae artists, and fans at various locations throughout Kingston including the University of the West Indies campus and JAMPRO, a government agency that aims to encourage business growth.

Many of Reggae Revival’s popular musicians are already successful such as Protoje, Kabaka Pyramid, and Chronixx, but the Manifesto team continues to campaign for independence to create their own label and promotional tools through the Manifesto network. Self-reliance is at the core of the movement, says Dutty Bookman.

He mentioned many musicians from previous generations who were trapped in poverty and connects their struggles to the plight of black people who were harmed by global capitalist organizations.

The wounds of colonialism and modernity deeply mark the living conditions of many Jamaicans. Bookman’s comments echoed the concerns born from centuries of operating within an oppressive system and the belief among members of Manifesto Jamaica and Reggae Revival that they must become the future guardians of Jamaican music to avoid further abuse.

When other natural resources in their land were taken away, culture emerged as the place where ideological self-determination began.

The Jamaican Manifesto is about education, exposure, and empowering young people and letting them know that art is a choice. Rather than having many young people fall into the criminal world, they know that they have other options.

The Jamaican Manifesto and its musical wing Reggae Revival envision a society that recognizes, respects and values the contribution of the creative industries.

The importance of the arts and cultural industries in modern society lies in three interrelated ways: their ability to create and circulate products that influence knowledge, understanding; their role as systems for managing creativity and knowledge; and their effect as agents of economic, social and cultural change.

One Love

What is Reggae Revival’s creative output?

Chronixx said in an interview that “All the music that we have been releasing, I look at all of those songs as one song. A progressive song. Just different verses. Different lines. My songs are just merely lines in that greater song.”

Jamaica’s national motto ‘Out of many, One People’ also applies to any music and culture. Musicologist Christopher Small writes in his book ‘Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening’: “To music is to take part, in any capacity, in a musical performance, whether by performing, by listening, by rehearsing or practicing, by providing material for performance (what is called composing) or by dancing.”

What the Reggae Revival works and their relationship with Jamaican culture show is that the cultural context itself plays a part in providing material. History, religion, folklore, and context all play a role in Jamaican music and culture. This follows the Rastafari concept of Livity, or the oneness of all living things such as the song “One Love” by Bob Marley. The song became a symbol of Rastafari politics that set an example for many Revival artists in conveying their messages.

Ancient-Present: “Come Ketch di Riddim”

Intertextual and intercontextual references are common in Jamaican music especially through the use of riddims or instrumental music tracks.

Riddim is an interesting contextualized cultural production because of the class-based component in its use. Riddim helped many poor singers early in their careers who could not afford to have their own bands. Singing over riddim gave them such a connection to the collective musical experience. The significance of riddims comes from the fact that they can be used interchangeably with new singers and new lyrics over riddims that have been recorded years or decades before.

So what’s new? According to Chronixx, he doesn’t glorify newness or what people call originality: “I don’t glorify new-ness. And what people call ‘originality.’ I don’t glorify in that. I glorify in continuity. Progress. Because progress don’t mean new. And continuity don’t mean new.” According to him, progress and continuity don’t have to be new. What riddims show is that what is new is often also old in the Jamaican context.

Many riddims were recorded instrumentally with studio bands in places like Studio One, the most famous studio in Jamaica during the golden era of reggae.

Singing over riddims is also often done by Revival artists. Jah 9’s ‘Steamers a Bubble’ uses the Roots Radics Apartment (1982) riddim. Protoje ‘Resist Not Evil’ uses the Militancy riddim. Chronixx’s ‘News Carrying Dread’ uses the Tenement Yard riddim. The contextual relationship here is that Chronixx comes to take the Tenement Yard riddim and bring his critique to the present. The riddim serves as a symbolic metaphor for the contemporary critique of technology and its adverse impact on communal experience. Chronixx not only used the old riddim but he also brought along the Inner Circle personnel in the making of the music video. This music video becomes a kind of meta performance of what the riddim does. Reggae Revival texts are not only present through the songs but also through visual arts and other creative endeavors that circulate globally through internet technology and social media. Bringing together audio and visual, past and present can coexist in the context of Jamaican music culture.

Revival blurs temporality in more ways than just riddims. Protoje’s album ‘Ancient Future’ (2015), for example, continues to bring the past into the present. In an interview, Protoje said that he wanted to bring 1970s reggae into his music, using his work to tell an alternative history of Jamaica. “Ancient Future is an attempt to bridge the gap between the past and the present, but also to push things forward,”

Protoje’s work draws on subaltern knowledge in the form of historical narratives that are mobilized to impact the present context.

By bringing the historic past into the present, it continues the vision of an ‘ancient future’ that disrupts the totality of modern progress that is taken for granted. As one of the most famous faces of Reggae Revival, he has become an example for other musicians to follow as the Revival movement grows.

Challenges and Contemplation

The efforts of the Jamaican Manifesto and Reggae Revival certainly did not go smoothly and encountered many obstacles. In the Babylon system these artists and intellectuals will continue to face challenges in realizing their vision and mission for Jamaican artists and other disadvantaged creative industry workers.

They do not deny that the colonial and post-colonial conditions faced by creative workers in Jamaica mean that they have certain challenges.

A long colonial history where the problems of the past are the problems of the present. It is still too difficult in the music industry to profit from cultural production. The problems of structural adjustment mean that the urban poor in Jamaica face long odds of advancement and the legacy of white supremacy still lingers.

The wounds of the past keep many people trapped in a protracted mire of grief and become an obstacle to true freedom. Mental slavery has become a symptom of people in the post-colonial region.

In an interview on I Never Knew TV at the end of 2024, Dutty Bookman said that the challenge of this movement is that Bad Mind syndrome and scarcity mindset (envy and feelings of rivalry) are a scourge in Jamaica. This makes it difficult for people to work with each other due to excessive suspicion. Bookman describes it as a mental illness that is endemic in Jamaica. The persistence of the Jamaican Manifesto and Reggae Revival’s aspiration for collectivity could be a symptom of melancholia because this is actually the ‘lack’ in Jamaica. This condition then becomes a desire engine that continues to spur the creativity of this group to fulfill the lack.

Hopefully, what Manifesto Jamaica and Reggae Revival have done will inspire all of us to “make music”, to take part in any capacity to respond to Bob Marley’s invitation to sing ‘Redemption Song’: “Won’t you help to sing, another song of freedom.”

Happy Reggae Month 2025. “Come Ketch on the Riddim!”

[Yedijah]

Show Comments (0)